Writing sample: problem statement and project status report

Context

When I started at Fastmail, we used a self-hosted GitLab instance as our git forge. In mid-2021, I was in charge of a project to move us from self-hosted GitLab to a private repo on GitHub.

Not long into that project, we hit a snag that ended up being a dealbreaker for the project. This is the email I sent to the engineering team with all the details about that. Ultimately we decided to scrap the project; I turned my attention to rewriting our deploy systems, as suggested toward the bottom of this email. In theory, this was a prerequisite to moving to GitHub, but in practice, it was not: Fastmail is still using self-hosted GitLab as I write this in mid-2025.

The email I sent is reproduced below the next header. The only changes I’ve made is that I have nerfed all links to internal documents/repos, and replaced them with empty anchor links.

Also, a tiny amount of additional context:

- GitLab calls “merge requests” what GitHub calls “pull requests,” if you’re

wondering what an MR is. GitLab also refers to MRs with bangs rather than

hashes, so

!123is shorthand for “merge request number 123”; GitHub uses “#123” to refer to both PRs and issues. - “hm” is, for unimportant (but not uninteresting) historical reasons, the name of the repo that holds all of the code for all of Fastmail

- “bort” is Fastmail’s chatops bot, which you talk to in order to deploy the site

- “Rik” is my friend Ricardo Signes, who was Fastmail’s CTO and my boss at the time.

Opinions wanted: current status of GitLab → GitHub project

Preface: this is a long email, but your opinion is needed; please read it and respond!

I have been working for a few weeks on GitHub Replaces GitLab project. This project has run into a few snags, and I am writing to get some input from you all before we decide the direction to go from here.

Backstory

Many people (but notably and loudly, I) have grumbled about GitLab over the years. Here’s what the project document has to say about problems with GitLab:

- GitLab has uneven performance (speed)

- GitLab has erratic crashes

- GitLab code review tools are subpar compared to GitHub

- GitLab permissions management is byzantine and nobody really understands it

- GitLab UI remains confusing (where is the button to do X?) even after years of use

And we think (or at least, suspect) that GitHub will be better than GitLab in a number of important ways:

- A more coherent UI (you don’t need to reload 3 times to see if your rebase has taken effect)

- More flexible permissions

- Better code review tools

(These should not be read as complete lists, either as cons of GitLab or pros of GitHub.)

Importantly, we knew when planning the project that moving to GitHub is going to involve a few tradeoffs:

- dependency on GitHub as an external service (we can’t ssh as root to the box it’s running on if something is being weird)

- needing to update deploy tooling such that we can still deploy Fastmail if GitHub is down or otherwise inaccessible

- having to mothball old MRs and losing some amount of metadata about them

- moving everyone’s cheese (we’ll need to migrate clones/forks, and everyone will need to point their local git remotes at new places, though we’ll provide tooling for that)

Unfortunately, there’s at least one big drawback that we (or at least, I), didn’t realize at the outset.

The Problem

GitHub does not have support for semi-linear merge history.

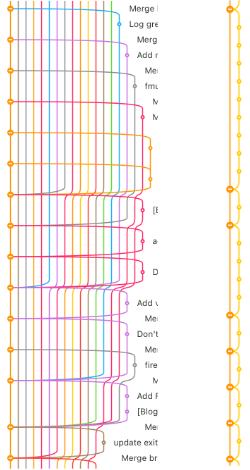

What does that mean, you ask? On the left is what hm.git history used to look like without semi-linear merges (this snapshot taken some time randomly in 2018), and on the right is what it looks like now.

What “semi-linear” means is that every branch must be rebased on top of master, and then is merged with a merge commit into master. This has a bunch of properties we like, and on which we (Rik and I, at least) are unwilling to concede, most of which boil down to “git history is readable”:

- Commits are read as the author intended, they are not squashed into a single commit.

- You get a merge commit, so you know exactly when a commit lands. (This morning, I merged a commit, 125d9397, written in March 2020, but you can tell it landed today because 03af7862 has an author date of this morning.)

- That merge commit contains a pointer back to the merge request, so later you can go find the discussion and look at the code review, should you need to. (I do this all the time.)

GitLab has an option to enforce semi-linear history (it’s turned on in most of our repos); GitHub does not have such an option. GitHub provides three options for the merge button:

- Create a merge commit (but does not require rebase first). This would mean our git history would look like it did before, in the left photo above.

- Rebase and squash. This is simply a non-starter: if you submit a merge request with 50 commits in it, this option would squash them all into a single commit, and that’s applied directly to master.

- Rebase and fast-forward. This keeps history strictly linear, with no merge commits at all. This would mean we lose the last two benefits listed above.

Discussion

The first idea I had was to coerce the merge button into doing what we want. I had a go at doing this, and it didn’t amount to much. The basic idea was to create a GitHub Action (a CI pipeline, basically) to enforce a particular git history shape. It didn’t quite work, and was pretty janky, so I’m leaving this option aside.

That leaves us with one real option, which is: disable the merge button in GitHub, and merge by some external means. This is what the rest of this email is about.

The world as it is now

You, a developer, want to get some changes into the world. Here’s what you do, right now.

- submit: submit a merge request

- review: have that code reviewed and approved

- merge: click the merge button, probably rebasing first

- deploy: get your changes into the world

Note that step four varies pretty widely across all of our repos (because remember, we’re talking about moving everything to GitHub, not just hm.git). For Fastmail deploys, step four is usually “ask bort to deploy”. For Pobox, it’s “run push-git”. For Topicbox, it’s “run deploy.sh”. Critically, for some of our repos, there is no step four. That is: we have some repos where the merge is the only thing that needs to happen, and there is no meaningful “and then put it into the world” step. (Some examples: [list of internal repos with links redacted].)

Possible solutions

The solutions we’ve come up with fall into basically two groups:

- Tag relevant MRs in some way when they’re ready to be merged, have automation look at the tags

- Explicitly tell the automation what to merge.

In the first world, you’d say, when going to merge, “mergebot, prepare master

for fastmail/hm” (or equivalently, bin/mergebot run fastmail/hm or similar).

This would look at all the PRs tagged “include-in-deploy”, ask you to confirm

that the list contains the PRs you expect, do all the rebasing and merging

required, and then push to master and tell you it’s done. (If this looks

familiar, it’s because mint-tag already does this for Cyrus builds and for

beta/staff Fastmail builds; mint-tag has already gained some smarts to do

semi-linear merges.)

In the second world, you’d instead say “mergebot, please merge fastmail/hm !123, !125, and !42”, and it would do basically the same thing.

In either of these solutions, we could probably combine the merge/deploy steps, such that you’d say, for Fastmail, “bort deploy fastmail/master” (which would assemble a master branch from PRs as it does for beta/staff now), or “bort deploy hm!123 hm!124 hm!42” (which is where we want to wind up eventually). But this has at least two big drawbacks: a) right now, Fastmail is the only repo we have that can be deployed by robot; and b) there are some repos that don’t have a deploy step at all (see above). For the latter case, we’d need to do something, so you’d have to get a robot involved where right now you can just click the button.

But wait

“But Michael,” I hear you saying, “this sounds like this project is turning into Rewrite All Of Our Deploy Systems rather than Update All Our Git Remotes.” That’s an astute question, dear reader, which is exactly why I’m writing this email! Because for me, the big question is: if we do want to make a bunch of changes to how deploys work, then do we really want to make them at the same time we Update All Our Git Remotes? Or phrased another way: if we want to make changes to how deploys work (and we do, in more ways than listed here), and we make those changes in our existing GitLab workflow, does that mitigate enough of the downsides of GitLab to make it so that switching to GitHub is no longer necessary/valuable?

(And perhaps more cynically/selfishly: if I am going to be the one doing the bulk of this work, will you, whose cheese I am moving, going to be low-key annoyed every time you’re not able to just click the dang merge button and instead have to get a robot involved?)

Questions for you

I have said many things, and will now try to put some questions in bullets for ease of answering:

- Do you even care where our repositories are hosted? (i.e., I suspect I feel more strongly about this project than most of you, and if everybody else says “eh, wevs” then I can just make a decision myself, in consultation with Rik!)

- How annoying, to you, would it be not to be able to click the merge button to get your changes onto master?

- Does the answer to question #2 change if right now, you don’t need to actually deploy your changes (and thus, you’d need to add an additional system where right now you can just click a button)?

I hope I have been clear; I am happy to expound further on any or all of this. Thanks in advance!